| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

Working With Naming and Directory Services in Oracle Solaris 11.1 Oracle Solaris 11.1 Information Library |

| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

Working With Naming and Directory Services in Oracle Solaris 11.1 Oracle Solaris 11.1 Information Library |

Part I About Naming and Directory Services

1. Naming and Directory Services (Overview)

Oracle Solaris Naming Services

Description of the DNS Naming Service

Description of Multicast DNS and Service Discovery

Description of the /etc Files Naming Service

Description of the NIS Naming Service

Description of the LDAP Naming Services

Description of the Name Service Switch

Naming Services: A Quick Comparison

2. Name Service Switch (Overview)

4. Setting Up Oracle Solaris Active Directory Clients (Tasks)

Part II NIS Setup and Administration

5. Network Information Service (Overview)

6. Setting Up and Configuring NIS (Tasks)

9. Introduction to LDAP Naming Services (Overview)

10. Planning Requirements for LDAP Naming Services (Tasks)

11. Setting Up Oracle Directory Server Enterprise Edition With LDAP Clients (Tasks)

12. Setting Up LDAP Clients (Tasks)

13. LDAP Troubleshooting (Reference)

14. LDAP Naming Service (Reference)

A Naming service performs lookups of stored information, such as:

Host names and addresses

User names

Passwords

Access permissions

Group membership, automount maps, and so on

This information is made available so that users can log in to their host, access resources, and be granted permissions. The name service information can be stored locally in various forms of database files, or in a central network-based repository or database.

Without a central naming service, each host would have to maintain its own copy of this information. Naming service information can be stored in files, maps, or database tables. If you centralize all data, administration becomes easier.

Naming services are fundamental to any computing network. Among other features, naming services provide functionality that does the following.

Associates (binds) names with objects

Resolves names to objects

Removes bindings

Lists names

Renames information

A network information service enables systems to be identified by common names instead of numerical addresses. This makes communication simpler because users do not have to remember and try to enter cumbersome numerical addresses like 192.168.0.0.

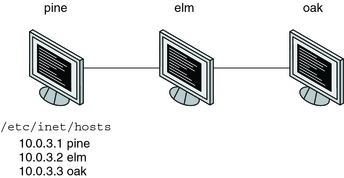

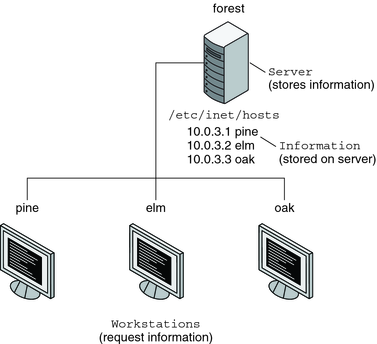

For example, take a network of three systems that are named, pine, elm, and oak. Before pine can send a message to either elm or oak, pine must know their numerical network addresses. For this reason, pine keeps a file, /etc/inet/hosts, that stores the network address of every system in the network, including itself.

Likewise, in order for elm and oak to communicate with pine or with each other, the systems must keep similar files.

In addition to storing addresses, systems store security information, mail data, network services information and so on. As networks offer more services, the list stored of information grows. As a result, each system might keep an entire set of files that are similar to /etc/inet/hosts.

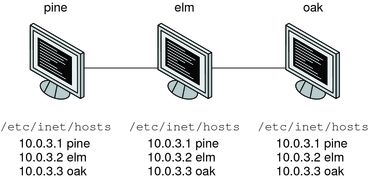

A network information service stores network information on a server, which can be queried by any system.

The systems are known as clients of the server. The following figure illustrates the client-server arrangement. Whenever information about the network changes, instead of updating each client's local file, an administrator updates only the information stored by the network information service. Doing so reduces errors, inconsistencies between clients, and the sheer size of the task.

This arrangement, of a server providing centralized services to clients across a network, is known as client-server computing.

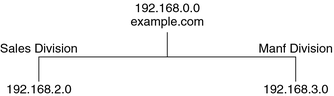

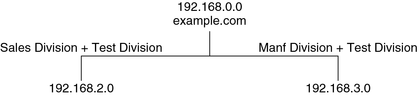

Although the main purpose of a network information service is to centralize information, the network information service can also simplify network names. For example, assume your company has set up a network which is connected to the Internet. The Internet has assigned your network the network address 192.168.0.0 and the domain name example.com. Your company has two divisions, Sales and Manufacturing (Manf), so its network is divided into a main network and one subnet for each division. Each net has its own address.

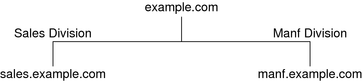

Each division could be identified by its network address, as shown above, but descriptive names made possible by naming services would be preferable.

Instead of addressing mail or other network communications to 198.168.0.0, mail could be addressed to example.com. Instead of addressing mail to 192.168.2.0 or 192.168.3.0, mail could be addressed to sales.example.com or manf.example.com.

Names are also more flexible than physical addresses. Physical networks tend to remain stable, but company organization tends to change.

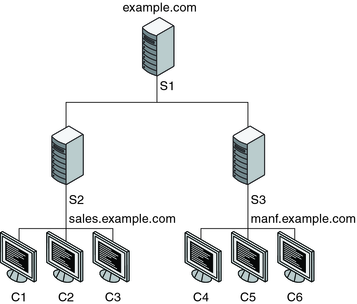

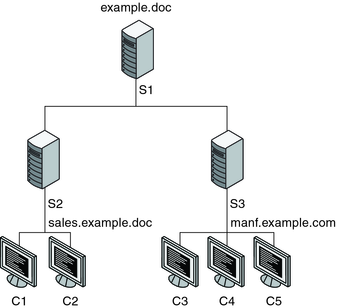

For example, assume that the example.com network is supported by three servers, S1, S2, and S3. Assume that two of those servers, S2 and S3, support clients.

Clients C1, C2, and C3 would obtain their network information from server S2. Clients C4, C5, and C6 would obtain information from server S3. The resulting network is summarized in the following table. The table is a generalized representation of that network but does not resemble an actual network information map.

Table 1-1 Representation of example.com Network

|

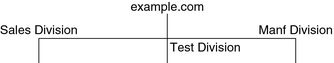

Now, assume that you create a third division, Testing, which borrowed some resources from the other two divisions, but did not create a third subnet. The physical network would then no longer parallel the corporate structure.

Traffic for the Test Division would not have its own subnet, but would instead be split between 192.168.2.0 and 192.168.3.0. However, with a network information service, the Test Division traffic could have its own dedicated network.

Thus, when an organization changes, its network information service can change its mapping as shown here.

Now, clients C1 and C2 would obtain their information from server S2. C3, C4, and C5 obtain information from server S3.

Subsequent changes in your organization would be accommodated by changes to the network information structure without reorganizing the network structure.