| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

STREAMS Programming Guide Oracle Solaris 11.1 Information Library |

| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

STREAMS Programming Guide Oracle Solaris 11.1 Information Library |

Part I Application Programming Interface

2. STREAMS Application-Level Components

3. STREAMS Application-Level Mechanisms

4. Application Access to the STREAMS Driver and Module Interfaces

7. STREAMS Framework - Kernel Level

8. STREAMS Kernel-Level Mechanisms

STREAMS Configuration Entry Points

STREAMS Initialization Entry Points

STREAMS Table-Driven Entry Points

Summarizing STREAMS Device Drivers

11. Configuring STREAMS Drivers and Modules

14. Debugging STREAMS-based Applications

B. Kernel Utility Interface Summary

STREAMS drivers have five different points of contact with the kernel:

Table 9-1 Kernel Contact Points

|

As with other SunOS 5 drivers, STREAMS drivers are dynamically linked and loaded when referred to for the first time. For example, when the system is initially booted, the STREAMS pseudo-tty slave pseudo-driver (pts(7D)) is loaded automatically into the kernel when it is first opened.

In STREAMS, the header declarations differ between drivers and modules. The word “module” is used in two different ways when talking about drivers. There are STREAMS modules, which are pushable nondriver entities, and there are kernel-loadable modules, which are components of the kernel. See the appropriate chapters in Writing Device Drivers.

The kernel configuration mechanism must distinguish between STREAMS devices and traditional character devices because system calls to STREAMS drivers are processed by STREAMS routines, not by the system driver routines. The streamtab pointer in the cb_ops(9S) structure provides this distinction. If it is NULL, there are no STREAMS routines to execute; otherwise, STREAMS drivers initialize streamtab with a pointer to a streamtab(9S) structure containing the driver's STREAMS queue processing entry points.

The initialization entry points of STREAMS drivers must perform the same tasks as those of non-STREAMS drivers. See Writing Device Drivers for more information.

In non-STREAMS drivers, most of the driver's work is accomplished through the entry points in the cb_ops(9S) structure. For STREAMS drivers, most of the work is accomplished through the message-based STREAMS queue processing entry points.

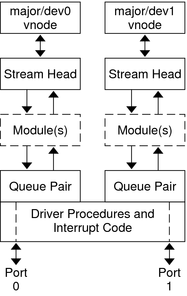

Figure 9-1 shows multiple streams (corresponding to minor devices) connecting to a common driver. There are two distinct streams opened from the same major device. Consequently, they have the same streamtab and the same driver procedures.

Figure 9-1 Device Driver Streams

Multiple instances (minor devices) of the same driver are handled during the initial open for each device. Typically, a driver stores the queue address in a driver-private structure that is uniquely identified by the minor device number. (The DDI/DKI provides a mechanism for uniform handling of driver-private structures; see ddi_soft_state(9F)). The q_ptr of the queue points to the private data structure entry. When the messages are received by the queue, the calls to the driver put and service procedures pass the address of the queue, enabling the procedures to determine the associated device through the q_ptr field.

STREAMS guarantees that only one open or close can be active at a time per major/minor device pair.

STREAMS device drivers have processing routines that are registered with the framework through the streamtab structure. The put procedure is a driver's entry point, but it is a message (not system) interface. STREAMS drivers and STREAMS modules implement these entry points similarly, as described in Entry Points.

The stream head translates write(2) and ioctl(2) calls into messages and sends them downstream to be processed by the driver's write queue put(9E) procedure. read is seen directly only by the stream head, which contains the functions required to process system calls. A STREAMS driver does not check system interfaces other than open and close, but it can detect the absence of a read indirectly if flow control propagates from the stream head to the driver and affects the driver's ability to send messages upstream.

For read-side processing, when the driver is ready to send data or other information to a user process, it prepares a message and sends it upstream to the read queue of the appropriate (minor device) stream. The driver's open routine generally stores the queue address corresponding to this stream.

For write-side (or output) processing, the driver receives messages in place of a write call. If the message cannot be sent immediately to the hardware, it may be stored on the driver's write message queue. Subsequent output interrupts can remove messages from this queue.

A driver is at the end of a stream. As a result, drivers must include standard processing for certain message types that a module might be able to pass to the next component. For example, a driver must process all M_IOCTL messages; otherwise, the stream head blocks for an M_IOCNAK, M_IOCACK, or until the timeout (potentially infinite) expires. If a driver does not understand an ioctl(2), an M_IOCNAK message is sent upstream.

Messages that are not understood by the drivers should be freed.

The stream head locks up the stream when it receives an M_ERROR message, so driver developers should be careful when using the M_ERROR message.

Most hardware drivers have an interrupt handler routine. You must supply an interrupt routine for the device's driver. The interrupt handling for STREAMS drivers is not fundamentally different from that for other device drivers. Drivers usually register interrupt handlers in their attach(9E)entry point, using ddi_add_intr(9F). Drivers unregister the interrupt handler at detach time using ddi_remove_intr(9F).

The system also supports software interrupts. The routines ddi_add_softintr(9F) and ddi_remove_softintr(9F) register and unregister (respectively) soft-interrupt handlers. A software interrupt is generated by calling ddi_trigger_softintr(9F).

See Writing Device Drivers for more information.

STREAMS drivers can prevent unloading through the standard driver detach(9E) entry point.