| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

STREAMS Programming Guide Oracle Solaris 11.1 Information Library |

| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

STREAMS Programming Guide Oracle Solaris 11.1 Information Library |

Part I Application Programming Interface

2. STREAMS Application-Level Components

3. STREAMS Application-Level Mechanisms

4. Application Access to the STREAMS Driver and Module Interfaces

7. STREAMS Framework - Kernel Level

8. STREAMS Kernel-Level Mechanisms

Message Allocation and Freeing

Bidirectional Data Transfer Example

Flushing According to Priority Bands

Driver and Module Service Interfaces

Service Interface Library Example

11. Configuring STREAMS Drivers and Modules

14. Debugging STREAMS-based Applications

B. Kernel Utility Interface Summary

STREAMS provides the means to implement a service interface between any two components in a stream, and between a user process and the topmost module in the stream. A service interface is a set of primitives defined at the boundary between a service user and a service provider (see Figure 8-5). Rules define a service and the allowable state transitions that result as these primitives are passed between the user and the provider. These rules are typically represented by a state machine. In STREAMS, the service user and provider are implemented in a module, driver, or user process. The primitives are carried bidirectionally between a service user and provider in M_PROTO and M_PCPROTO messages.

PROTO messages (M_PROTO and M_PCPROTO) can be multiblock. The second through last blocks are of type M_DATA. The first block in a PROTO message contains the control part of the primitive in a form agreed upon by the user and provider. The block is not intended to carry protocol headers. (Upstream PROTO messages can have multiple PROTO blocks at the start of the message, although its use is not recommended. getmsg(2) compacts the blocks into a single control part when sending to a user process.) The M_DATA block contains any data part associated with the primitive. The data part can be processed in a module that receives it, or it can be sent to the next stream component, along with any data generated by the module. The contents of PROTO messages and their allowable sequences are determined by the service interface specification.

PROTO messages can be sent bidirectionally (upstream and downstream) on a stream and between a stream and a user process. putmsg(2) and getmsg(2) system calls are analogous to write(2) and read(2) except that the former allow both data and control parts to be (separately) passed, and they retain the message boundaries across the user-stream interface. putmsg(2) and getmsg(2) separately copy the control part (M_PROTO or M_PCPROTO block) and data part (M_DATA blocks) between the stream and user process.

An M_PCPROTO message normally is used to acknowledge primitives composed of other messages. M_PCPROTO ensures that the acknowledgement reaches the service user before any other message. If the service user is a user process, the stream head will only store a single M_PCPROTO message, and discard subsequent M_PCPROTO messages until the first one is read with getmsg(2).

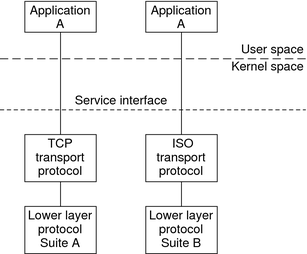

Figure 8-4 Protocol Substitution

By defining a service interface through which applications interact with a transport protocol, you can substitute a different protocol below the service interface that is completely transparent to the application. In Figure 8-4, the same application can run over the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and the ISO transport protocol. Of course, the service interface must define a set of services common to both protocols.

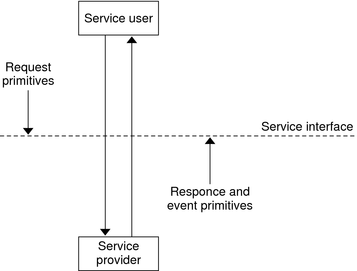

The three components of any service interface are the service user, the service provider, and the service interface itself, as seen in Figure 8-5.

Figure 8-5 Service Interface

Typically, an application makes requests of a service provider using some well-defined service primitive. Responses and event indications are also passed from the provider to the user using service primitives.

Each service interface primitive is a distinct STREAMS message that has two parts, a control part and a data part. The control part contains information that identifies the primitive and includes all necessary parameters. The data part contains user data associated with that primitive.

An example of a service interface primitive is a transport protocol connect request. This primitive requests the transport protocol service provider to establish a connection with another transport user. The parameters associated with this primitive can include a destination protocol address and specific protocol options to be associated with that connection. Some transport protocols also allow a user to send data with the connect request. A STREAMS message is used to define this primitive. The control part identifies the primitive as a connect request and includes the protocol address and options. The data part contains the associated user data.

The service interface library example presented here includes four functions that enable a user do the following:

Establish a stream to the service provider and bind a protocol address to the stream

Send data to a remote user

Receive data from a remote user

Close the stream connected to the provider

First, the structure and constant definitions required by the library are shown in the following code. These typically reside in a header file associated with the service interface.

The defined structures describe the contents of the control part of each service interface message passed between the service user and service provider. The first field of each control part defines the type of primitive being passed.

Example 8-16 Service Interface Library Header File

/*

* Primitives initiated by the service user.

*/

#define BIND_REQ 1 /* bind request */

#define UNITDATA_REQ 2 /* unitdata request */

/*

* Primitives initiated by the service provider.

*/

#define OK_ACK 3 /* bind acknowledgement */

#define ERROR_ACK 4 /* error acknowledgement */

#define UNITDATA_IND 5 /* unitdata indication */

/*

* The following structure definitions define the format

* of the control part of the service interface message

* of the above primitives.

*/

struct bind_req { /* bind request */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always BIND_REQ */

t_uscalar_t BIND_addr; /* addr to bind */

};

struct unitdata_req { /* unitdata request */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always UNITDATA_REQ */

t_scalar_t DEST_addr; /* destination addr */

};

struct ok_ack { /* positiv acknowledgement*/

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always OK_ACK */

};

struct error_ack { /* error acknowledgement */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always ERROR_ACK */

t_scalar_t UNIX_error; /* UNIX systemerror code */

};

struct unitdata_ind { /* unitdata indication */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always UNITDATA_IND */

t_scalar_t SRC_addr; /* source addr */

};

/* union of all primitives */

union primitives {

t_scalar_t type;

struct bind_req bind_req;

struct unitdata_req unitdata_req;

struct ok_ack ok_ack;

struct error_ack error_ack;

struct unitdata_ind unitdata_ind;

};

/* header files needed by library */

#include <stropts.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <errno.h>

Five primitives are defined. The first two represent requests from the service user to the service provider.

Asks the provider to bind a specified protocol address. It requires an acknowledgement from the provider to verify that the contents of the request were syntactically correct.

Asks the provider to send data to the specified destination address. It does not require an acknowledgement from the provider.

The three other primitives represent acknowledgements of requests, or indications of incoming events, and are passed from the service provider to the service user.

Informs the user that a previous bind request was received successfully by the service provider.

Informs the user that a nonfatal error was found in the previous bind request. It indicates that no action was taken with the primitive that caused the error.

The following code is part of a module that illustrates the concept of a service interface. The module implements a simple service interface and mirrors the service interface library example. The following rules pertain to service interfaces.

Modules and drivers that support a service interface must act upon all PROTO messages and not pass them through.

Modules can be inserted between a service user and a service provider to manipulate the data part as it passes between them. However, these modules cannot alter the contents of the control part (PROTO block, first message block) nor alter the boundaries of the control or data parts. That is, the message blocks comprising the data part can be changed, but the message cannot be split into separate messages nor combined with other messages.

In addition, modules and drivers must observe the rule that high-priority messages are not subject to flow control and forward them accordingly.

The service interface primitives are defined in the declarations shown in the following example:

Example 8-17 Service Primitive Declarations

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/param.h>

#include <sys/stream.h>

#include <sys/errno.h>

/* Primitives initiated by the service user */

#define BIND_REQ 1 /* bind request */

#define UNITDATA_REQ 2 /* unitdata request */

/* Primitives initiated by the service provider */

#define OK_ACK 3 /* bind acknowledgement */

#define ERROR_ACK 4 /* error acknowledgement */

#define UNITDATA_IND 5 /* unitdata indication */

/*

* The following structures define the format of the

* stream message block of the above primitives.

*/

struct bind_req { /* bind request */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always BIND_REQ */

t_uscalar_t BIND_addr; /* addr to bind */

};

struct unitdata_req { /* unitdata request */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always UNITDATA_REQ */

t_scalar_t DEST_addr; /* dest addr */

};

struct ok_ack { /* ok acknowledgement */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always OK_ACK */

};

struct error_ack { /* error acknowledgement */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always ERROR_ACK */

t_scalar_t UNIX_error; /* UNIX system error code*/

};

struct unitdata_ind { /* unitdata indication */

t_scalar_t PRIM_type; /* always UNITDATA_IND */

t_scalar_t SRC_addr; /* source addr */

};

union primitives { /* union of all primitives */

long type;

struct bind_req bind_req;

struct unitdata_req unitdata_req;

struct ok_ack ok_ack;

struct error_ack error_ack;

struct unitdata_ind unitdata_ind;

};

struct dgproto { /* structure minor device */

short state; /* current provider state */

long addr; /* net address */

};

/* Provider states */

#define IDLE 0

#define BOUND 1

In general, the M_PROTO or M_PCPROTO block is described by a data structure containing the service interface information in this example, union primitives.

The module recognizes two commands:

Give this stream a protocol address (for example, give it a name on the network). After a BIND_REQ is completed, data from other senders will find their way through the network to this particular stream.

Send data to the specified address.

The module generates three messages:

A positive acknowledgement (ack) of BIND_REQ.

A negative acknowledgement (nak) of BIND_REQ.

Data from the network has been received.

The acknowledgement of a BIND_REQ informs the user that the request was syntactically correct (or incorrect if ERROR_ACK). The receipt of a BIND_REQ is acknowledged with an M_PCPROTO to ensure that the acknowledgement reaches the user before any other message. For example, if a UNITDATA_IND comes through before the bind is completed, the application cannot send data to the proper address

The driver uses a per-minor device data structure, dgproto, which contains the following:

Current state of the service provider IDLE or BOUND.

Network address that has been bound to this stream.

The module open procedure is assumed to have set the write queue q_ptr to point at the appropriate private data structure, although this is not shown explicitly.

The write put procedure, protowput(), is shown in the following example:

Example 8-18 Service Interface protoput Procedure

static int protowput(queue_t *q, mblk_t *mp)

{

union primitives *proto;

struct dgproto *dgproto;

int err;

dgproto = (struct dgproto *) q->q_ptr; /* priv data struct */

switch (mp->b_datap->db_type) {

default:

/* don't understand it */

mp->b_datap->db_type = M_ERROR;

mp->b_rptr = mp->b_wptr = mp->b_datap->db_base;

*mp->b_wptr++ = EPROTO;

qreply(q, mp);

break;

case M_FLUSH: /* standard flush handling goes here ... */

break;

case M_PROTO:

/* Protocol message -> user request */

proto = (union primitives *) mp->b_rptr;

switch (proto->type) {

default:

mp->b_datap->db_type = M_ERROR;

mp->b_rptr = mp->b_wptr = mp->b_datap->db_base;

*mp->b_wptr++ = EPROTO;

qreply(q, mp);

return;

case BIND_REQ:

if (dgproto->state != IDLE) {

err = EINVAL;

goto error_ack;

}

if (mp->b_wptr - mp->b_rptr !=

sizeof(struct bind_req)) {

err = EINVAL;

goto error_ack;

}

if (err = chkaddr(proto->bind_req.BIND_addr))

goto error_ack;

dgproto->state = BOUND;

dgproto->addr = proto->bind_req.BIND_addr;

mp->b_datap->db_type = M_PCPROTO;

proto->type = OK_ACK;

mp->b_wptr=mp->b_rptr+sizeof(structok_ack);

qreply(q, mp);

break;

error_ack:

mp->b_datap->db_type = M_PCPROTO;

proto->type = ERROR_ACK;

proto->error_ack.UNIX_error = err;

mp->b_wptr = mp->b_rptr+sizeof(structerror_ack);

qreply(q, mp);

break;

case UNITDATA_REQ:

if (dgproto->state != BOUND)

goto bad;

if (mp->b_wptr - mp->b_rptr !=

sizeof(struct unitdata_req))

goto bad;

if(err=chkaddr(proto->unitdata_req.DEST_addr))

goto bad;

putq(q, mp);

/* start device or mux output ... */

break;

bad:

freemsg(mp);

break;

}

}

return(0);

}

The write put procedure, protowput(), switches on the message type. The only types accepted are M_FLUSH and M_PROTO. For M_FLUSH messages, the driver performs the canonical flush handling (not shown). For M_PROTO messages, the driver assumes that the message block contains a union primitive and switches on the type field. Two types are understood: BIND_REQ and UNITDATA_REQ.

For a BIND_REQ, the current state is checked; it must be IDLE. Next, the message size is checked. If it is the correct size, the passed-in address is verified for legality by calling chkaddr. If everything checks, the incoming message is converted into an OK_ACK and sent upstream. If there was any error, the incoming message is converted into an ERROR_ACK and sent upstream.

For UNITDATA_REQ, the state is also checked; it must be BOUND. As above, the message size and destination address are checked. If there is any error, the message is discarded. If all is well, the message is put in the queue, and the lower half of the driver is started.

If the write put procedure receives a message type that it does not understand, either a bad b_datap->db_type or bad proto->type, the message is converted into an M_ERROR message and is then sent upstream.

The generation of UNITDATA_IND messages (not shown in the example) would normally occur in the device interrupt if this is a hardware driver or in the lower read put procedure if this is a multiplexer. The algorithm is simple: the data part of the message is prefixed by an M_PROTO message block that contains a unitdata_ind structure and is sent upstream.

To change a message type, use the following rules:

You can only change the M_IOCTL family of message types to other M_IOCTL message types.

M_DATA, M_PROTO, and M_PCPROTO are dependent on the modules, driver and service provider interfaces defined.

A message type should not be changed if the reference count > 1.

The data of a message should not be modified if the reference count > 1.

All other message types are interchangeable as long as sufficient space has been allocated in the data buffer of the message.