| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

Oracle Solaris 11.1 Administration: Security Services Oracle Solaris 11.1 Information Library |

| Skip Navigation Links | |

| Exit Print View | |

|

Oracle Solaris 11.1 Administration: Security Services Oracle Solaris 11.1 Information Library |

1. Security Services (Overview)

Part II System, File, and Device Security

2. Managing Machine Security (Overview)

3. Controlling Access to Systems (Tasks)

4. Virus Scanning Service (Tasks)

5. Controlling Access to Devices (Tasks)

6. Verifying File Integrity by Using BART (Tasks)

7. Controlling Access to Files (Tasks)

Part III Roles, Rights Profiles, and Privileges

8. Using Roles and Privileges (Overview)

Role-Based Access Control (Overview)

RBAC: An Alternative to the Superuser Model

RBAC Elements and Basic Concepts

Privileged Applications and RBAC

Applications That Check UIDs and GIDs

Applications That Check for Privileges

Applications That Check Authorizations

Security Considerations When Directly Assigning Security Attributes

Usability Considerations When Directly Assigning Security Attributes

Privileges Protect Kernel Processes

Administrative Differences on a System With Privileges

Privileges and System Resources

How Privileges Are Implemented

Expanding a User or Role's Privileges

Restricting a User or Role's Privileges

Assigning Privileges to a Script

9. Using Role-Based Access Control (Tasks)

10. Security Attributes in Oracle Solaris (Reference)

Part IV Cryptographic Services

11. Cryptographic Framework (Overview)

12. Cryptographic Framework (Tasks)

Part V Authentication Services and Secure Communication

14. Using Pluggable Authentication Modules

17. Using Simple Authentication and Security Layer

18. Network Services Authentication (Tasks)

19. Introduction to the Kerberos Service

20. Planning for the Kerberos Service

21. Configuring the Kerberos Service (Tasks)

22. Kerberos Error Messages and Troubleshooting

23. Administering Kerberos Principals and Policies (Tasks)

24. Using Kerberos Applications (Tasks)

25. The Kerberos Service (Reference)

Role-based access control (RBAC) is a security feature for controlling user access to tasks that would normally be restricted to the root role. By applying security attributes to processes and to users, RBAC can divide up superuser capabilities among several administrators. Process rights management is implemented through privileges. User rights management is implemented through RBAC.

For a discussion of process rights management, see Privileges (Overview).

For information about RBAC tasks, see Chapter 9, Using Role-Based Access Control (Tasks).

For reference information, see Chapter 10, Security Attributes in Oracle Solaris (Reference).

In conventional UNIX systems, the root user, also referred to as superuser, is all-powerful. Programs that run as root, or setuid programs, are all-powerful. The root user has the ability to read and write to any file, run all programs, and send kill signals to any process. Effectively, anyone who can become superuser can modify a site's firewall, alter the audit trail, read confidential records, and shut down the entire network. A setuid program that is hijacked can do anything on the system.

Role-based access control (RBAC) provides a more secure alternative to the all-or-nothing superuser model. With RBAC, you can enforce security policy at a more fine-grained level. RBAC uses the security principle of least privilege. Least privilege means that a user has precisely the amount of privilege that is necessary to perform a job. Regular users have enough privilege to use their applications, check the status of their jobs, print files, create new files, and so on. Capabilities beyond regular user capabilities are grouped into rights profiles. Users who are expected to do jobs that require some of the capabilities of superuser assume a role that includes the appropriate rights profile.

RBAC collects superuser capabilities into rights profiles. These rights profiles are assigned to special user accounts that are called roles. A user can then assume a role to do a job that requires some of superuser's capabilities. Predefined rights profiles are supplied with Oracle Solaris software. You create the roles and assign the profiles.

Rights profiles can provide broad capabilities. For example, the System Administrator rights profile enables an account to perform tasks that are not related to security, such as printer management and cron jobs. Rights profiles can also be narrowly defined. For example, the Cron Management rights profile manages at and cron jobs. When you create roles, the roles can be assigned broad capabilities or narrow capabilities or both.

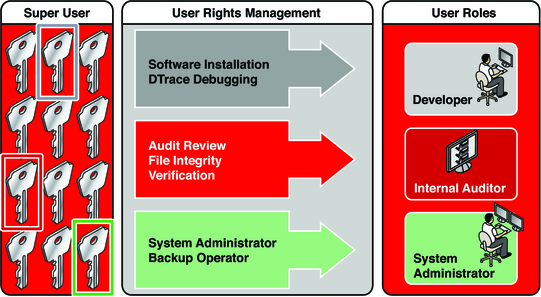

The following figure illustrates how RBAC can distribute rights to trusted parties.

Figure 8-1 RBAC Distribution of Rights

In the RBAC model, superuser creates one or more roles. The roles are based on rights profiles. Superuser then assigns the roles to users who are trusted to perform the tasks of the role. Users log in with their user name. After login, users assume roles that can run restricted administrative commands and graphical user interface (GUI) tools.

The flexibility in setting up roles enables a variety of security policies. Although few roles are shipped with Oracle Solaris, a variety of roles can easily be configured. You can base most roles on rights profiles of the same name:

root – A powerful role that is equivalent to the root user. However, this root cannot log in. A regular user must log in, then assume the assigned root role. This role is configured by default.

System Administrator – A less powerful role for administration that is not related to security. This role can manage file systems, mail, and software installation. However, this role cannot set passwords.

Operator – A junior administrator role for operations such as backups and printer management.

You might also want to configure one or more security roles. Three rights profiles and their supplementary profiles handle security: Information Security, User Security, and Zone Security. Network security is a supplementary profile in the Information Security rights profile.

These roles do not have to be implemented. Roles are a function of an organization's security needs. One strategy is to set up roles for special-purpose administrators in areas such as security, networking, or firewall administration. Another strategy is to create a single powerful administrator role along with an advanced user role. The advanced user role would be for users who are permitted to fix portions of their own systems.

The superuser model and the RBAC model can co-exist. The following table summarizes the gradations from superuser to restricted regular user that are possible in the RBAC model. The table includes the administrative actions that can be tracked in both models. For a summary of the effect of privileges alone on a system, see Table 8-2.

Table 8-1 Superuser Model Contrasted With the RBAC With Privileges Model

|

The RBAC model in Oracle Solaris introduces the following elements:

Authorization – A permission that enables a user or role to perform a class of actions that require additional rights. For example, security policy at installation gives regular users the solaris.device.cdrw authorization. This authorization enables users to read and write to a CD-ROM device. For a list of authorizations, see the /etc/security/auth_attr file.

Privilege – A discrete right that can be granted to a command, a user, a role, or a system. Privileges enable a process to succeed. For example, the proc_exec privilege allows a process to call execve(). Regular users have basic privileges. To see your basic privileges, run the ppriv -vl basic command. For more command options, see Administrative Commands for Handling Privileges.

Security attributes – An attribute that enables a process to perform an operation. In a typical UNIX environment, a security attribute enables a process to perform an operation that is otherwise forbidden to regular users. For example, setuid and setgid programs have security attributes. In the RBAC model, authorizations and privileges are security attributes in addition to setuid and setgid programs. These attributes can be assigned to a user. For example, a user with the solaris.device.allocate authorization can allocate a device for exclusive use. Privileges can be placed on a process. For example, a process with the file_flag_set privilege can set immutable, no-unlink, or append-only file attributes.

Privileged application – An application or command that can override system controls by checking for security attributes. In a typical UNIX environment and in the RBAC model, programs that use setuid and setgid are privileged applications. In the RBAC model, programs that require privileges or authorizations to succeed are also privileged applications. For more information, see Privileged Applications and RBAC.

Rights profile – A collection of security attributes that can be assigned to a role or to a user. A rights profiles can include authorizations, directly assigned privileges, commands with security attributes, and other rights profiles. Profiles that are within another profile are called supplementary rights profiles. Rights profiles offer a convenient way to group security attributes.

Role – A special identity for running privileged applications. The special identity can be assumed by assigned users only. In a system that is run by roles, including the root role, superuser is unnecessary. Superuser capabilities are distributed to different roles. For example, in a two-role system, security tasks would be handled by a security role. The second role would handle system administration tasks that are not security-related. Roles can be more fine-grained. For example, a system could include separate administrative roles for handling the Cryptographic Framework, printers, system time, file systems, and auditing.

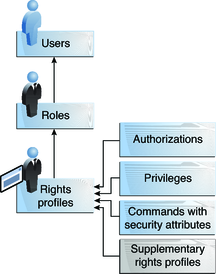

The following figure shows how the RBAC elements work together.

Figure 8-2 RBAC Element Relationships

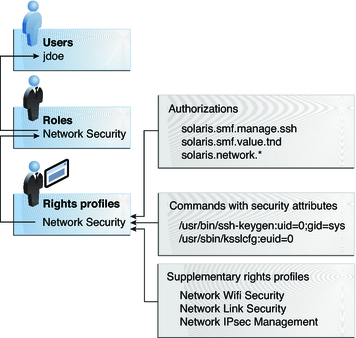

The following figure uses the Network Security role and the Network Security rights profile to demonstrate RBAC relationships.

Figure 8-3 Example of RBAC Element Relationships

The Network Security role is used to manage IPsec, wifi, and network links. The role is assigned to the user jdoe. jdoe can assume the role by switching to the role, and then supplying the role password. The administrator can customize the role to accept the user password rather than the role password.

In Figure 8-3, the Network Security rights profile is assigned to the Network Security role. The Network Security rights profile contains supplementary profiles that are evaluated in order, Network Wifi Security, Network Link Security, and Network IPsec Management. These supplementary profiles fill out the role's primary tasks.

The Network Security rights profile has three directly assigned authorizations, no directly assigned privileges, and two commands with security attributes. The supplementary rights profiles have directly assigned authorizations, and two of them have commands with security attributes. In the Network Security role, jdoe has all assigned authorizations in these profiles, and can run all the commands with security attributes in these profiles. jdoe can administer network security.

Oracle Solaris provides administrators with a great deal of flexibility when configuring security. As installed, the software does not allow for privilege escalation. Privilege escalation occurs when a user or process gains more administrative rights than were intended to be granted. In this sense, privilege means any security attribute, not just privileges.

Oracle Solaris software includes security attributes that are assigned to the root role only. With other security protections in place, an administrator might assign attributes that are designed for the root role to other accounts, but such assignment must be made with care.

The following rights profile and set of authorizations can escalate the privileges of a non-root account.

Media Restore rights profile – This profile exists, but is not part of any other rights profile. Because Media Restore provides access to the entire root file system, its use is a possible escalation of privilege. Deliberately altered files or substitute media could be restored. By default, the root role includes this rights profile.

solaris.*.assign authorizations – These authorizations exist, but are not assigned to any rights profile or account. An account with a solaris.*.assign authorization can assign security attributes to others that the account itself is not assigned. For example, a role with the solaris.profile.assign authorization can assign rights profiles to other accounts that the role itself is not assigned. By default, only the root role has solaris.*.assign authorizations.

Best practice is to assign solaris.*.delegate authorizations, not solaris.*.assign authorizations. A solaris.*.delegate authorization enables the delegater to assign other accounts only those security attributes that the delegater possesses. For example, a role that is assigned the solaris.profile.delegate authorization can assign rights profiles that the role itself is assigned to other users and roles.

For escalations that affect the privilege security attribute, see Prevention of Privilege Escalation.

An authorization is a discrete right that can be granted to a role or to a user. Authorizations enforce policy at the user application level.

While authorizations can be assigned directly to a role or to a user, best practice is to include authorizations in a rights profile. The rights profile is then added to a role, and the role is assigned to a user. For an example, see Figure 8-3.

Authorizations that include the words delegate or assign enable the user or role to assign security attributes to others.

To prevent escalation of privilege, do not assign an account an assign authorization.

A delegate authorization enables the delegater to assign others only those security attributes that the delegater possesses. For example, a role that is assigned the solaris.profile.delegate authorization can assign to others rights profiles that the role itself is assigned.

An assign authorization enables the assigner to assign others security attributes that the account does not possess. For example, a role with the solaris.profile.assign authorization can assign to others any rights profile.

The solaris.*.assign authorizations are delivered, but are not included in any profile. By default, only the root role has the solaris.*.assign authorizations.

RBAC-compliant applications can check a user's authorizations prior to granting access to the application or specific operations within the application. This check replaces the check in conventional UNIX applications for UID=0. For more information about authorizations, see the following sections:

Privileges enforce security policy in the kernel. The difference between authorizations and privileges concerns the level at which the security policy is enforced. Without the proper privilege, a process can be prevented from performing privileged operations by the kernel. Without the proper authorizations, a user might be prevented from using a privileged application or from performing security-sensitive operations within a privileged application. For a fuller discussion of privileges, see Privileges (Overview).

Applications and commands that can override system controls are considered privileged applications. Security attributes such as UID=0, privileges, and authorizations make an application privileged.

Privileged applications that check for root (UID=0) or some other special UID or GID have long existed in the UNIX environment. The rights profile mechanism enables you to isolate commands that require a specific ID. Instead of changing the ID on a command that anyone can access, you can place the command with assigned security attributes in a rights profile. A user or role with that rights profile can then run the program without having to become superuser.

IDs can be specified as real or effective. Assigning effective IDs is preferred over assigning real IDs. Effective IDs are equivalent to the setuid feature in the file permission bits. Effective IDs also identify the UID for auditing. However, because some shell scripts and programs require a real UID of root, real UIDs can be set as well. For example, the reboot command requires a real rather than an effective UID. If an effective ID is not sufficient to run a command, you need to assign the real ID to the command.

Privileged applications can check for the use of privileges. The RBAC rights profile mechanism enables you to specify the privileges for specific commands that require security attributes. Then, you can isolate the command with assigned security attributes in a rights profile. A user or role with that rights profile can then run the command with just the privileges that the command requires to succeed.

Commands that check for privileges include the following:

Kerberos commands, such as kadmin, kprop, and kdb5_util

Network commands, such as ipadm, routeadm, and snoop

File and file system commands, such as chmod, chgrp, and mount

Commands that control processes, such as kill, pcred, and rcapadm

To add commands with privileges to a rights profile, see How to Create a Rights Profile and the profiles(1) man page. To determine which commands check for privileges in a particular profile, see How to View All Defined Security Attributes.

Oracle Solaris additionally provides commands that check authorizations. By definition, the root user has all authorizations. Therefore, the root user can run any application. Applications that check for authorizations include the following:

Audit administration commands, such as auditconfig and auditreduce

Printer administration commands, such as lpadmin and lpfilter

The batch job-related commands, such as at, atq, batch, and crontab

Device-oriented commands, such as allocate, deallocate, list_devices, and cdrw.

To test a script or program for authorizations, see Example 9-23. To write a program that requires authorizations, see About Authorizations in Developer’s Guide to Oracle Solaris 11 Security.

A rights profile is a collection of security attributes that can be assigned to a role or user to perform tasks that require administrative rights. A rights profile can include authorizations, privileges, commands with assigned security attributes, and other rights profiles. Privileges that are assigned in a rights profile are in effect for all commands. Rights profiles also contain entries to reduce or extend the initial inheritable set, and to reduce the limit set of privileges.

For more information about rights profiles, see the following sections:

A role is a special type of user account from which you can run privileged applications. Roles are created in the same general manner as user accounts. Roles have a home directory, a group assignment, a password, and so on. Rights profiles and authorizations give the role administrative capabilities. Roles cannot inherit capabilities from other roles or other users. Discrete roles parcel out superuser capabilities, and thus enable more secure administrative practices.

When a user assumes a role, the role's attributes replace all user attributes. Role information is stored in the passwd, shadow, and user_attr databases. The actions of roles can be audited. For detailed information about setting up roles, see the following sections:

A role can be assigned to more than one user. All users who can assume the same role have the same role home directory, operate in the same environment, and have access to the same files. Users can assume roles from the command line by running the su command and supplying the role name and a password. By default, users authenticate to a role by supplying the role's password. The administrator can configure the system to enable a user to authenticate by supplying the user's password. For the procedure, see How to Enable a User to Use Own Password to Assume a Role.

A role cannot log in directly. A user logs in, and then assumes a role. Having assumed a role, the user cannot assume another role without first exiting their current role. Having exited the role, the user can then assume another role.

The fact that root is a role in Oracle Solaris prevents anonymous root login. If the profile shell command, pfexec, is being audited, the audit trail contains the login user's real UID, the roles that the user has assumed, and the actions that the role performed. To audit the system or a particular user for role operations, see How to Audit Roles.

The rights profiles that ship with the software are designed to map to roles. For example, the System Administrator rights profile can be used to create the System Administrator role. To configure a role, see How to Create a Role.

Users and roles can run privileged applications from a profile shell. A profile shell is a special shell that recognizes the security attributes that are included in a rights profile. Administrators can assign a profile shell to a specific user as a login shell, or the profile shell is started when that user runs the su command to assume a role. In Oracle Solaris every shell has a profile shell counterpart. For example, the profile shell counterparts to the Bourne shell (sh), bash shell (bash), and Korn shell (ksh) are the pfsh, pfbash, and pfksh shells, respectively. For the list of profile shells, see the pfexec(1) man page.

Users who have been directly assigned a rights profile and whose login shell is not a profile shell must invoke a profile shell to run the commands with security attributes. For usability and security considerations, see Security Considerations When Directly Assigning Security Attributes.

All commands that are executed in a profile shell can be audited. For more information, see How to Audit Roles.

Name service scope is an important concept for understanding RBAC. The scope of a role might be limited to an individual host. Alternatively, the scope might include all hosts that are served by a naming service such as LDAP. The name service scope for a system is specified in the name switch service, svc:/system/name-service/switch. A lookup stops at the first match. For example, if a rights profile exists in two name service scopes, only the entries in the first name service scope are used. If files is the first match, then the scope of the role is limited to the local host.

Typically, a user obtains administrative capabilities through a role. Authorizations, privileges, and privileged commands are grouped into a rights profile. The rights profile is included in a role, and the role is assigned to a user.

Direct assignment of rights profiles and security attributes is also possible:

Rights profiles, privileges, and authorizations can be assigned directly to users.

Privileges and authorizations can be assigned directly to users and roles.

However, direct assignment of privileges is not a secure practice. Users and roles with a directly assigned privilege could override security policy wherever this privilege is required by the kernel. A more secure practice is to assign the privilege as a security attribute of a command in a rights profile. Then, that privilege is available only for that command by someone who has that rights profile.

Since authorizations act at the user level, direct assignment of authorizations can be less dangerous than direct assignment of privileges. However, authorizations can enable a user to perform highly secure tasks, such as assign audit flags.

Direct assignment of rights profiles and security attributes can affect usability:

Directly assigned privileges and authorizations, and the commands and authorizations in a directly assigned rights profile, must be interpreted by a profile shell to be effective. By default, users are not assigned a profile shell.

The user must remember to open a profile shell and execute the commands in that shell.

Singly assigning authorizations is not scalable. And, directly assigned authorizations might not be sufficient to perform a task. The task might require privileged commands.

Rights profiles are designed to bundle authorizations and privileged commands together. They are also scalable.